At least four generations of this family had no fingerprints. Apu Sarkar shows me his palm during a video call. At first glance, there is nothing unusual about the Bangladeshi resident’s appearance, but upon closer inspection, I notice unusually smooth fingertips.

Apoo is 22 years old and lives with his family in a village in the northern part of the country, in the district of Nator. Until recently he worked as a caretaker. Both his father and grandfather were farmers.

The men in the Apu family appear to have an extremely rare genetic abnormality found in very few people in the world: they have no fingerprints. Grandfather Apu did not think this was important. “I don’t think he saw any problem with it at all,” Apu says.

But in recent years, tiny patterns on the fingertips, known as dermatoglyphs, have become extremely valuable and necessary information for various biometric agencies. Now, they are used at every step – from passing through airport security to voting and unlocking a cell phone.

In 2008, when Apu was still a boy, Bangladesh introduced national identity cards, which were required for every adult citizen of the country. To register such a document, it was necessary to submit a thumbprint. Stunned government officials didn’t understand how to issue a card to Father Apu Amalu Sarkar. As a result, he received an identity card with the stamp “WITHOUT FINGERPRINTS”.

But in 2010, it became necessary to provide fingerprints to obtain a passport and driver’s license. It was a long time before Amal was able to get a passport – and only after he provided a medical certificate about his unique condition.

Amala Sarkar has no fingerprints on her fingertips. We explain quickly, simply and clearly what happened, why it matters and what happens next. Translation: episodes The end of the story: Advertising in podcasts.

However, Amal never used this passport to travel abroad, in part because he was afraid of problems at airport security. And although he needs to ride a motorcycle for work, he has never been able to get a license. “I paid the required amount, passed the exam, but they wouldn’t give me a license because I couldn’t pass the fingerprint test,” says Amal.

To prove that he has a driver’s license, Amal carries a receipt for the fee he paid, but not all policemen accept it: he has already had to pay a fine twice. Although he explained why he couldn’t get the document – even showing the police his bare fingertips – the fines were not canceled. “I always feel very uncomfortable in these situations,” says Amal.

In 2016, the family faced a new problem. People who wanted to buy a new SIM card for their cell phone had to give their fingerprints, which the shops were obliged to compare with the national database. “When I needed a SIM card, they didn’t understand what was happening. Their program kept freezing when I put my finger on the fingerprint sensor,” Apu smiles. As a result, he was never able to buy a SIM card, and now all the men in the family use cell phone numbers registered in his mother’s name.

The rare genetic disorder this family suffers from is called adermatoglyphia. She was first mentioned in 2007, when a woman unable to enter the United States sought the help of Swiss dermatologist Peter Itin. Her face matched the photo in her passport, but American border officials were unable to take her fingerprints. Because she simply did not have any.

After examining the situation, Professor Itin found that other members of her family had the same strange condition – smooth fingertips and a reduced number of sweat glands in their hands. Itin, along with another dermatologist, Eli Shprecher, and graduate student Yana Nusbek, examined the DNA of 16 members of this family – seven of whom had fingerprints and nine of whom did not. “Similar cases are extremely rare; there is data on only a very small number of families,” Itin said in an interview with the BBC.

Amal and Apu: The lack of fingerprints is inherited from our father. In 2011, these scientists identified the SMARCAD1 gene, a mutation of which led to the absence of fingerprints in nine members of this Swiss family. The mutation does not appear to have any other health consequences.

Professor Sprecher explains that no one knew about the mutation for so long because science was not aware of the existence of the gene itself. The mutation changes only a specific part of the gene, which seems to have no purpose, just like the gene as a whole, says the expert.

The disease has an official name, adermatoglyphia, but Professor Itin called it, less scientifically but more understandably: “delayed migration disorder”. Uncle Apu Sarker Gopesh lives 350 kilometers away from the country’s capital and has struggled for several years to obtain a passport. “In the last few years, I had to go to Dakar four or five times for them to believe that I really have this disease,” says Gopesh.

Recently, the office where he works started using fingerprints to clock in before the start of a shift, so he had to convince management to let him sign in the attendance book the old-fashioned way. The doctor in Bangladesh diagnosed the members of this family with “congenital palmoplantar keratoderma” which, according to Professor Itin, has evolved into adermatoglyphia. This condition can also cause dry skin and reduced sweating of the palms and feet – these symptoms are also called sarcoidosis. Itin is willing to help members of this family undergo genetic testing to learn more about their disease.

The test results will help the Sarkers understand what exactly is happening in their bodies, but they will still find it difficult to live in the modern world without fingerprints. However, society is increasingly demanding biometric information from them that they simply do not have.

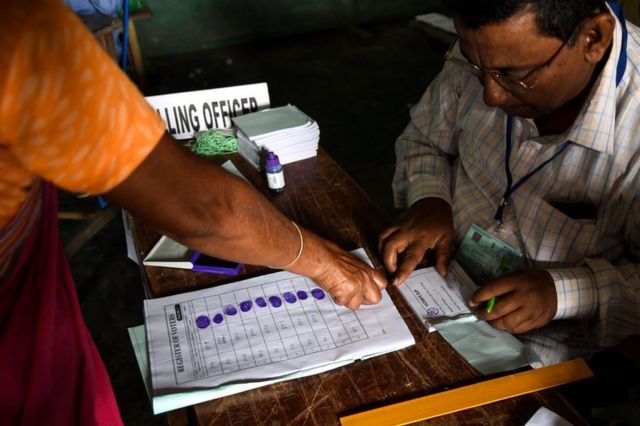

In India, voters are fingerprinted before voting. Amal Sarkar says he had no problems for most of his life, but his children will have a much harder time. “I can’t do anything about it, I inherited it,” he says. “But now my son and I are facing many difficulties because of it.”

Amal and Apu provided the authorities with medical documentation of their illness and were able to obtain identification cards. However, these cards use different biometric information: scans of their iris and facial parameters. But they still can’t buy a new SIM card or get a driver’s license. And getting a passport is a very long and arduous process. “I am tired of explaining the situation over and over again. I have asked many people what to do, but no one can say anything clearly,” Aapu admits.

“Some say to go to court. If nothing else works, I will have to do that. Apu is hoping to get a passport because he really wants to go abroad. However, he has not yet started the registration process. Photos courtesy of the Sarker family.